Bard, Copilot, AI Companion, and the Privacy Mountain

Google, Microsoft, and Zoom are set to make a mountain out of privacy issues at the university. Is it climbable?

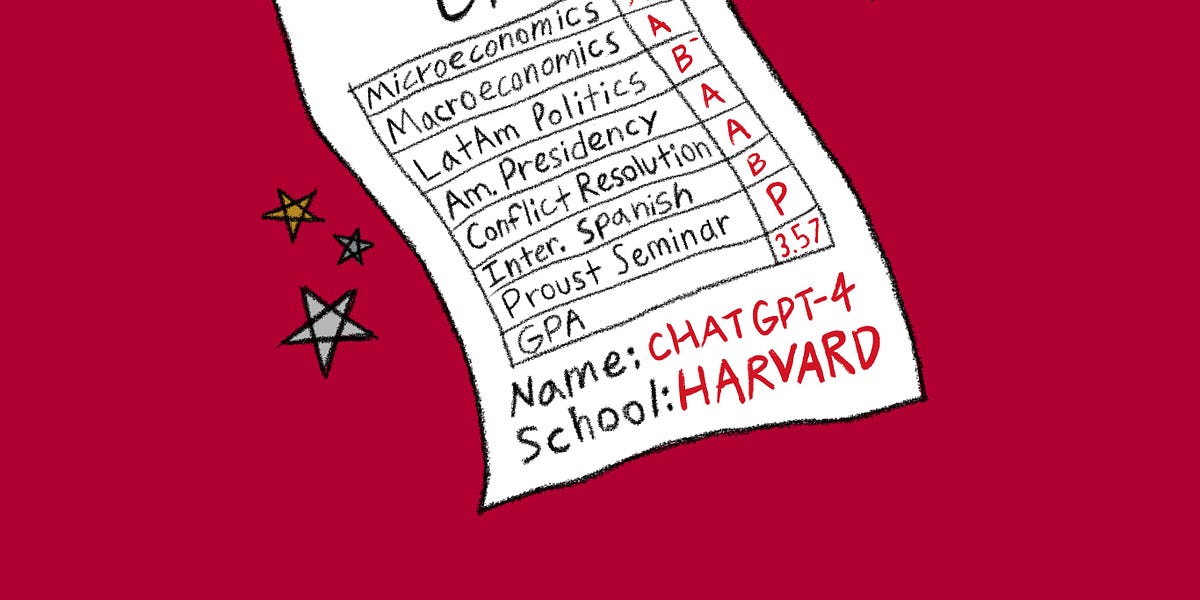

[image created with Dall-E 2 via Bing’s Image Creator]

Welcome to AutomatED: the newsletter on how to teach better with tech.

Each week, I share what I have learned — and am learning — about AI and tech in the university classroom. What works, what doesn't, and why.

In this week’s edition, I discuss some intriguing AI developments coming from Google, Microsoft, and Zoom, as well as how they make a mountain out of privacy issues. Next week, I try to climb it.

🌡️ Bard Ups the Ante

This week, Google announced the release of a new version of its Bard AI tool. The key change with the new version is that it is integrated via Bard Extensions with Google Workspace — the apps and services from Google that many of us use on a daily basis, from Gmail to Docs, Sheets, Drive, Maps, Flights, and even YouTube.

I have been experimenting with the new Bard integration and I think future iterations of it will be game-changers for many professors. In short, it enables us to efficiently retrieve, organize, and express information from disparate sources in the Google Workspace in response to queries in the Bard interface.

Here are some of the things it can help you do:

You can ask for a list of all of the students who you need to follow up with via Gmail (assuming you emailed about this in the past), as well as a one sentence description of what you promised them or what they owe you.

You can ask for an analysis of all of your Gmail communications with each struggling student, as well as your Docs-stored feedback to them, in order to develop a personalized plan grounded in the course content (stored in your Drive) to get them back on track.

You can ask for a detailed one-paragraph or one-page summary of a complex grant application that you have stored across various items in Docs and Sheets, in order to describe it in a new grant application, an email to a colleague, or a job application.

You can ask for a new plan for how to proceed in teaching a module of a course, given the plan expressed in the syllabus you have stored in Docs and the slower-than-expected pace at which you have been able to cover the topics (as represented by the Slides and Powerpoints stored in your Drive).

You can ask for instructional YouTubes related to topics you plan to teach in your courses — based on your lesson plans — such that each week’s content is paired with a relevant optional video “reading.”

While some uses for the integration of Bard with Google Workspace will consist of us typing in queries manually — just as you can upload a slew of relevant files and type in a query with ChatGPT4’s Advanced Data Analysis right now — the endgame will be automated workflows that link all of these various services in ways that depend little on your prior awareness of how they can be linked in a given case. Need to help a struggling student with all the resources you have available to you in the Google Workspace? Bard has you covered and will connect all the relevant services to streamline the intervention.

Of course, some of these automated workflows are already available to us, especially if we make use of Zapier and project management tools like Asana. (We will be posting templates and guides for building more advanced workflows in the coming months in the premium part of the AutomatED Learning Community.)

🔜 Copilot and AI Companion Gaining Steam

Soon, Microsoft will be able to tell a similar story, at least once their Microsoft 365 Copilot is released. Microsoft 365 Copilot will use AI to unify and integrate Office suite programs like Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook, and Teams along with files via OneDrive. Just today, Microsoft announced that a “Copilot icon” will be released this coming Tuesday to create a consistent “user experience” across all of Microsoft 365 in anticipation of the release on November 1. Windows Copilot, which has similar functions but on the side of the operating system, will be released this coming Tuesday.

But surely I am getting ahead of myself. By now, I bet you are thinking that both the new Bard and the forthcoming Copilots are privacy nightmares, in general and especially in the university setting. And you would be right! But wait, there’s more!

Two weeks ago, Zoom announced updates to their AI Companion. With current functionality, it enables users to

watch recordings faster through highlights and smart chapters, and review summaries and next steps, so they can easily catch up on a missed meeting. In the meeting, if enabled by the meeting host, attendees can catch up quickly without disrupting the meeting flow by discreetly submitting questions via the in-meeting AI Companion side panel to receive an AI-generated answer on what they missed. Post-meeting, hosts can receive an automated meeting summary to share with attendees and those who were unable to attend a meeting. These capabilities help team members who may be in different time zones catch up asynchronously.

Many of these functions are those that had been the purview of third-party apps like Fireflies.ai and Otter.ai. Like many companies before it (Amazon, I am looking at you), Zoom has been watching these third-party apps from its monopolistic perch, taking notes, and scheming to retain its position as the one-stop-shop.

Zoom’s AI Companion also aims to undercut Slack’s dominance in the team chat space by automating chat response creation, integrating responses and dialogue with meeting transcripts, and linking both chats and meetings to email (via Zoom Mail). So, for instance, if you have a meeting on Zoom, you will be able to use its automatically generated transcript to quickly convey the relevant bits of its content to people who did not attend, either via chat or via emails that are drafted by generative AI. These functions are coming down the pike in the next few months.

Professors could use this technology in many creative ways after recording every class and student meeting with Zoom (whether virtual or in-person). Here are some options:

Students who miss class or arrive late can catch up on what they missed on their own device without disrupting others.

Students can get summaries of segments of the lecture content if the details are bogging them down or if they want to see if their notes match.

Students can get remedial help with integrations between these segment summaries and other AI tools, like chatbots.

Professors can automate email communication with students on the basis of the specific questions they asked in class or conversations that occurred in office hours.

The list of clever use-cases in the university teaching context is very long. But, again, so is the list of privacy issues.

⛰️ The Privacy Mountain

There are two dimensions along which pre-existing privacy issues related to student data are going to multiply in this new paradigm.

First, with it becoming easier and more useful for professors to run a great quantity of detailed personal student information through Google, Microsoft, Zoom, and the like, the security and privacy compliance of these AI-fueled ecosystems becomes much more important.

No longer will your Google Workspace be largely filled with your work and your correspondence — it will soon be dominated by student information produced by these various integrations.

Second, if there is more student information in an ecosystem like Google’s, then it is more important to secure its connections to the outside.

As the case of Zoom trying to compete with Fireflies.ai and Otter.ai shows, often third-party app makers are ahead of the dominant app makers in developing useful new tools that can be integrated with the dominant apps, but these third-party apps are often not as secure — or, at least, not as well-vetted (by university IT teams) — as the dominant ones.

But perhaps the greatest risk comes from human error on behalf of the professor. Sure, we have all sent emails to the wrong recipients before, but automated workflows can multiply some of these risks.

The core problem here is a moral one: many of the most useful ways in which a professor could use these AI-fueled ecosystems would push a great quantity of detailed and personal student information through them, which wrongfully runs the risk of exposing this information to various parties who gain access to the ecosystems themselves or who gain access to the information when it leaves the ecosystems.

In the US context, there are various other layers of concern. On the federal level, there is the FERPA law, which prohibits certain uses of student information and data by institutions that receive funding from the Department of Education. The law is complex, but the short story is that the personally identifiable education records of students 18 years and older cannot be shared or stored beyond the classroom (or university-approved spaces like, say, Canvas) without students’ explicit written consent.

Beyond laws like FERPA, many universities have their own rules and regulations on the use and storage of student data. Although there is some consistency across institutions, there is a lot of variation based on the environment and history of each particular institution.

So, what is a professor to do?

I see five main options:

Do not use ecosystems like Google’s to handle student information at all.

Limit your use of these ecosystems to categories of student information that face no privacy concerns in the first place.

Change the consent paradigm by working to get much more explicit consent from your students to enable the use of the ecosystems with a wider range of their information (including sensitive and personally identifiable records).

Pseudonymize or anonymize student information before entry into the ecosystems and/or before the ecosystems interface with other apps.

Some combination of the above.

In next week’s piece, I will give my take on each of these options, as well as some of the institutional changes at universities that I think these issues necessitate.

I am going to argue that we really need to avoid options 1 and 2, if we can. I am going to try to charge up the mountain.