RE: Vinsel, Chiang, Clark, Botstein, Pines, boyd

The plausible, implausible, and uncertain claims about AI made by the second six of CHE's recent panel.

[image created with DALL-E 2 via Microsoft Bing Image Creator]

Welcome to AutomatED: the newsletter on how to teach better with tech.

Each week, I share what I have learned — and am learning — about AI and tech in the university classroom. What works, what doesn't, and why.

Let's reflect on the claims that six professors and university administrators made recently in the Chronicle about the effect of AI on higher education.

On May 25th, the Chronicle of Higher Education published an article that contains the brief thoughts on AI of twelve prominent figures in higher education.

Earlier this week, I provided an opinionated response to the first half of the panel. I highlighted claims that I find plausible, implausible, and less certain than they assume, and I explain why I agree or disagree.

Today, I do the same with the second half of the panel.

Lee Vinsel

One of their plausible claims:

The first stories to emerge around new technologies typically offer hyperbolic assessments of powers, promises, and threats. And they are almost always wrong.

Vinsel brings receipts on this one, including a reference to the 2019 book Bubbles and Crashes: The Boom and Bust of Technological Innovation by Brent Goldfarb and David A. Kirsch (which covers nearly 100 technologies over 150 years). It is clear that the stories around the impact of new technologies are typically hyperbolic and tend to be off the mark.

One of their implausible claims:

Historians of computing will tell you about similar bubbles around AI in the 1960s and 1980s, which, when the promises of the technologies failed to arrive, were followed by “AI winters,” periods when funding for research into artificial intelligence all but dried up.

Yet we still see hysterically positive and negative appraisals of ChatGPT. Sam Altman, chief executive of ChatGPT’s maker, OpenAI, told reporters that AI would “eclipse the agricultural revolution, the industrial revolution, the internet revolution all put together.” Meanwhile, the Future of Life Institute published an open letter calling for a six-month ban on training AI systems more powerful than GPT-4 because they would threaten humanity. At the time of this writing, nearly 30,000 people have signed the letter.

Why, after so many technology bubbles that have ended in pops and deflations, do these same histrionic scripts continue to play out?

I take it that Vinsel thinks that the present stories about AI are significantly mistaken about its promise and/or risks, hence ‘hysterically’ and ‘histrionic’. While I agree with Vinsel that most stories about the power of new technologies are overly positive or negative — indeed, maybe they are “almost always wrong” — I think it is implausible to think that the present stories about AI are. We are already seeing the massive effects of AI in the last few years, in a wide variety of domains relevant to those of us in higher education. Teaching, research, and administration are all being affected, and it is still early days in the development of AI like GPT-4 and explorations of its use cases.

My question for Vinsel is this: why not think that this current AI revolution is comparable to those very real revolutions you list (agricultural, industrial, internet)? It is one thing for a soldier to rightfully ignore repeated false alarms of enemy offensives, but it is another for her to ignore palpable evidence that she has a real offensive on her hands. Simply because most claimed revolutions are not actual revolutions, it does not follow that this one is not actual. What are the signs of a real revolution, if not broad and deep disruptions of fields like we are seeing with AI today?

Mung Chiang

One of their plausible claims:

Some have explored banning AI in education. That would be hard to enforce; it’s also unhealthy, as students will need to function in an AI-infused workplace upon graduation.

As we have seen, it is quite hard to make AI-immune take-home assignments, although we are still investigating various ways of doing so with our AI-immunity assignment challenge.

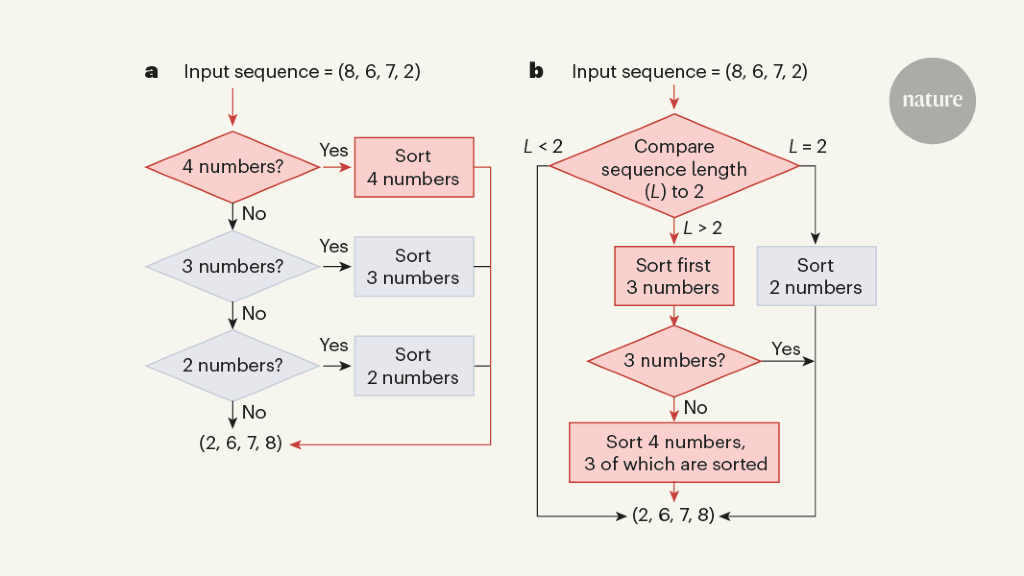

I also agree that students will need the skill to effectively use AI in many fields, and I think most professors need to learn how AI tools work in order to figure out whether and how to incorporate them in their course design. I discuss this at length in a separate piece. Here is the decision flowchart that arose from that earlier discussion, for those who prefer diagrams:

The process of assignment design in the age of AI.

One of their implausible claims:

Pausing AI research would be even less practical, not least because AI is not a well-defined, clearly demarcated area. Colleges and companies around the world would have to stop any research that involves math. One of my Ph.D. advisers, Professor Tom Cover, did groundbreaking work in the 1960s on neural networks and statistics, not realizing they would later become useful in what others call AI.

This reason for the impracticality of pausing AI research is implausible. Sure, it is hard to predict which technical results will be relevant to the development of new and powerful AI tools. However, it is a separate question whether it is practical to pause AI research that intends to develop AI that is potentially dangerous, say.

As an analogy, it was hard to predict that early research into nuclear fission would lead to research into and the development of nuclear bombs. Nonetheless, it is practical to pause (or control) research into and development of nuclear bombs, as we do today.

One of the uncertain claims they present as certain:

We need entrepreneurs to invent competing AI systems and maximize choices outside the big-tech oligopoly. Some of them will invent ways to break big data.

Like many technologies, AI is born neutral but can be abused, especially in the name of the “collective good.” The gravest risk of AI is its abuse by authoritarian regimes.

This seems to assume that intended negative effects of AI are the only serious risks. Authoritarian regimes abusing AI is a serious risk because they intend to use it to negative effect. Entrepreneurs, on the other hand, are not a serious risk because they do not intend to use it to negative effect, or so Chiang seems to assume.

Yet, even if we assume entrepreneurs have sufficiently good intentions, it is not clear that they will not — by accident — produce negative effects. It is unclear to me if this is not a serious risk, too.

Rick Clark

One of their plausible claims:

Colleges that invest in and rigorously train AI to generate automated, high-quality responses to student inquiries will free admission staff members from perfunctory, time-consuming, and low-return work, allowing them to focus instead on higher level, mission-aligned efforts. That shift will increase professional-growth opportunities and network building, both of which will foster job satisfaction and retention.

This claim of Clark is plausible to me because it aligns with my own experiences writing grant applications (ahem) and because, as noted last week, there is some evidence that people prefer completing some tasks with AI tools than without. The study providing this evidence, written by Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang, concerns “mid-level professional writing tasks,” and the authors report that ChatGPT “increases job satisfaction and self-efficacy” and “restructures tasks towards idea-generation and editing and away from rough-drafting.” I look forward to many more studies like this one in the coming months.

One of the uncertain claims they present as certain:

The landscape of college admissions is bifurcated. The “haves” — colleges with big national reputations and large endowments — tout escalating numbers of applicants and precipitous drops in admit rates. Conversely, at the “have-nots,” discount rates rise, the threat of layoffs and furloughs becomes more common, and the pressure to reverse fiscal shortfalls expands with each cycle.

Behind the numbers are people: admissions deans, directors, and their staffs. And while their day-to-day pressures are sharply different, their posture is the same: broken.

Two recent Chronicle articles captured the causes: low salaries, stunted career progress, and unreasonable work-life balance, to name a few. Answers, however, have been in short supply. While AI is not a panacea, it is a significant part of the solution.

[…]

Many view AI as a threat. But when it comes to college admissions, I have no doubt that AI will be an agent of redemption.

Two claims here need to be distinguished: (i) that AI will be an “agent of redemption” in relieving the day-to-day pressures of higher education admissions that Clark discusses, like repetitive and unfulfilling work poring over applications, and (ii) that AI will be an “agent of redemption” in addressing the fiscal issues of the “have-nots.”

While it is more likely that (i) is true, per the above, it is not at all clear that (ii) is true. Like many innovations, AI may be yet another case where the “haves” are able to more quickly and more effectively leverage it than the “have-nots,” leaving the “have-nots” no better off, fiscally, than they were before. It is not clear if AI will help level the playing field.

Leon Botstein

One of their plausible claims:

The current furor about AI is too little and too late, and has turned into the sort of hysteria that has accompanied most if not all technological revolutions in the West. The printing press inspired fear and panic among the minuscule portion of the European population that had been literate. Printing led to mass literacy, which then was held responsible for the Terror during the French Revolution; pessimism surrounded mass print journalism and fiction. Balzac and Flaubert reveled in depicting the corrosive influence cheap romance novels and newspapers had on their readers. The current debate over AI is vaguely reminiscent of other past controversies about the influence of recording (gramophone and radio), and later in the 20th century, film and television. We are still struggling with understanding the impact of the computer, the internet, and the smartphone. But we should remember, as a cautionary tale, that the railroad was once considered deleterious to health and an engine of cultural decline.

I agree that the changes wrought by AI are often treated as bad or deleterious, without enough focus on the positive potential of AI. Many of the people who are consistently negative about the potential of AI are the least informed about its capabilities. (There are, of course, many exceptions to this rule, including importantly those AI researchers concerned about long-term terrible outcomes.) It also is plausible that the present moment mirrors the prior ones noted by Botstein.

Personally, I have found my own experimentation with AI tools to be crucial to shaping my opinions about them. This is why I used my early access to GPT-3 several years ago to show my family, friends, and colleagues its potential — there is nothing like seeing it for yourself. I recommend the same to professors as they work on their fall syllabi.

One of their implausible claims:

For those concerned about students’ abusing the power of ChatGPT, we just have to take the time and make sure we know our students and have worked with them closely enough to both inspire them to do their own work and take pride in work that is their own. We will have to become smarter in detecting manipulation and the deceptive simulation of reality.

As a teacher of students from a wide range of university contexts, I think this is naive for a number of reasons. First, there are many courses where the professor cannot work closely with students, due to factors like class sizes or asynchronicity. Second, students taking pride in their work is hard to inculcate in the span of a single semester, especially if students are not willingly taking the course in question (because it is a prerequisite, a general education requirement, or otherwise). Third, there are other more effective ways to address the concern that students will abuse the power of ChatGPT, as we have discussed here.

One of the uncertain claims they present as certain:

How can we help them find joy, meaning, and value, and also gainful employment, when machines will do so much of what we do now? AI will eliminate far more employment than the automatic elevator, E-ZPass, and computer-controlled manufacturing already have. Work, employment, and compensation will have to be redefined, but in a more systematic manner than after the agricultural and industrial revolutions. Without that effort, the ideals of freedom, individuality, and the protection of civil liberties will be at risk.

As I wrote earlier this week in response to Philip Kitcher, “the standard view of economists is that labor-saving technologies have not, to date, decreased labor force participation rates, and other factors are its primary determinants.”

Darryll J. Pines

One of their plausible claims:

Like the calculator, the personal laptop, smartphones, and Zoom, AI may soon become integral to our enterprise.

We must, of course, confront the technology’s capability to increase plagiarism, the spread of misinformation, and confusion over intellectual-property rights, but the positive potential of AI deserves just as much of higher education’s attention as its pitfalls do.

I will not bore you with a reiteration of why I think this is plausible.

One of their implausible claims:

But higher ed has a long history of adapting to new events, needs, and technologies: Like the calculator, the personal laptop, smartphones, and Zoom, AI may soon become integral to our enterprise.

I am somewhat doubtful that higher education adapts to new events, needs, and technologies. In my experiences with higher education — from my time as an undergraduate through my PhD and onward — I have seen a lot of resistance to change. In particular, there is tendency towards ignorance of pedagogical and technological innovations. This is why I write pieces on how professors should use e-learning software to upgrade their boring content and on how to make the most of AI-enhanced voice transcription software. Indeed, it is why we are running the AI-immunity challenge: we have found many of our colleagues in denial about the capabilities of AI tools, denying basic facts about how they operate or what they can achieve.

So, while I think AI will eventually become integral to our enterprise, I think it is implausible that higher education will adapt in the sense of facilitating or embracing this change.

danah boyd

One of their plausible claims:

But let's not allow AI to distract us from the questions that should animate us: What is the role of higher education in today’s world? What societal project does higher education serve? And is this project viable in a society configured by late-stage capitalism? These are hard questions.

I agree that these are hard questions, and I agree that AI should not distract us from the questions that should animate us, including these. The risks and opportunities presented to higher education by AI are no more important than other serious risks and opportunities facing higher education.

One of their implausible claims:

I cannot seem to escape debates about how AI will change everything. They make me want to crawl into a cave. I nod along as my peers blast students for cheating with ChatGPT — then rave about how Bing Chat’s search function is a more effective research assistant than most students. The contradictions that surround new AI chatbots are fascinating, but the cacophonous polarities are excruciating, and obscure as much as they illuminate.

It is implausible that it is a contradiction to “blast students for cheating with ChatGPT” and then to “rave about how Bing Chat’s search function is a more effective research assistant than most students." Cheating with ChatGPT is disanalogous to using Bing Chat for research, as there are often pedagogical reasons to limit student’s capabilities to use AI tools, even if the tasks they are assigned could be completed effectively by AI tools.

It is not a contradiction to disapprove of a young student using a calculator for basic arithmetic activities and then rave about the power of Excel in a faculty meeting.

One of the uncertain claims they present as certain:

Technology mirrors and magnifies the good, the bad, and the ugly. But the technology itself is rarely the story. If we care about higher ed, the real question isn't: What will AI do to higher ed? Instead, we should ask: What can the hype and moral panic around AI teach us about higher ed?

It is not at all clear to me why “What will AI do to higher ed?” is not a real question, or a real question relative to “What can the hype and moral panic around AI teach us about higher ed?” I assume real questions are those that are important. (Or, perhaps in this context, those that are important if we care about higher education.) In either sense, both are real questions.

I granted above that the risks and opportunities presented to higher education by AI are no more important than other serious risks and opportunities facing higher education, but this does not imply that AI is not important. Especially since the hype is — in large part — real.